Tine After Tine: An Early History of the Fork

We explore the fork in ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome, meet the Byzantine Princess who brought it to Venice, and its blossoming love affair with pasta.

In the West, we’re more accustomed to eating with cutlery than we are with our hands. When it comes to breakfast, lunch, and dinner, knives, forks, and spoons are essential. In Britain, we have a lot of etiquette that accompanies each bite. An excerpt from Debrett’s illustrates this nicely:

‘The fork and spoon are the only things that should go into the mouth. Never lick the knife or eat off it. If using a knife and fork together, always keep the tines of the fork pointing downwards and push the food on to the fork. It may be necessary to use mashed potato to make peas stick to the fork but it is incorrect to turn the fork over and scoop….’ Blah, blah, blah.

But it wasn’t always so. There was, in fact, a time before cutlery. As Jonathan Swift wrote in 1738, ‘They say fingers were made before forks, and hands before knives.’ But forget about knives and spoons, each with their own history, and let’s focus on the fork.

The fork is the youngest of the three main eating implements, only becoming a staple at the dinner table from the 17th century onwards, and even then this was mainly concentrated to Western Europe.

The ancient fork

The word fork comes from the Latin furca, meaning ‘pitch fork’, though it’s unlikely the Romans and other ancient civilisations used table forks like we do today.

Mosaic of Poseidon.

In Egyptian antiquity, large bronze forks were used at religious ceremonies to lift up sacrificial offerings and, most likely, to look cool. Ceremonial forks were also used by the Greeks and Romans, though there are no mentions of table forks.

Greeks did use ‘flesh-forks’ to take meat out of boiling pots and hold it still while carving, and the Romans may have used fork-like instruments for similar purposes. There were many other ancient fork-like tools, including tridents and hay forks, but these were used by Gods and farmers, rather than gastronomes.

The Venetian fork

The first use of a modern fork in Europe is credited to Maria Argyropoulina around the years 1004/5. Maria was a Byzantine Princess who married the son of a Venetian Doge to strengthen political ties between the two powers. Coming from Constantinople, a much larger and more modern metropolis than Venice and other western cities, Maria brought with her many unusual practices, including the wearing of silks and jewellery, the burning of sweet herbs, bathing in rainwater, and of course, the fork.

St. Peter Damian. Possibly thinking about forks.

‘She did not touch her food with her hands’ wrote the Benedictine monk, Peter Damian, ‘but when her eunuchs had cut it up into pieces she daintily lifted them to her mouth with a small two-pronged gold fork.’

It’s believed that forks like this were used in Middle Eastern royal courts as far back as the 7th century and perhaps further, but in 11th century Italy, the Catholic Church condemned the practice, deeming it an affront to nature, and as having a corrupting influence on Western women. Maria would die from the plague shortly after arriving in Venice, a fate seen as punishment for her sins. Long after her death she was used as a cautionary tale about how the West should be careful of the decadent and depraved ways of the East.

The pasta fork

Table forks wouldn’t be mentioned again for three centuries, when they began to creep up more often in the inventories of the royals and the rich. Charles V of France, King from 1364-1380, had silver and gold forks that were used only for ‘eating mulberries and foods likely to stain the fingers’. But even then, forks wouldn’t be commonly used until two centuries later.

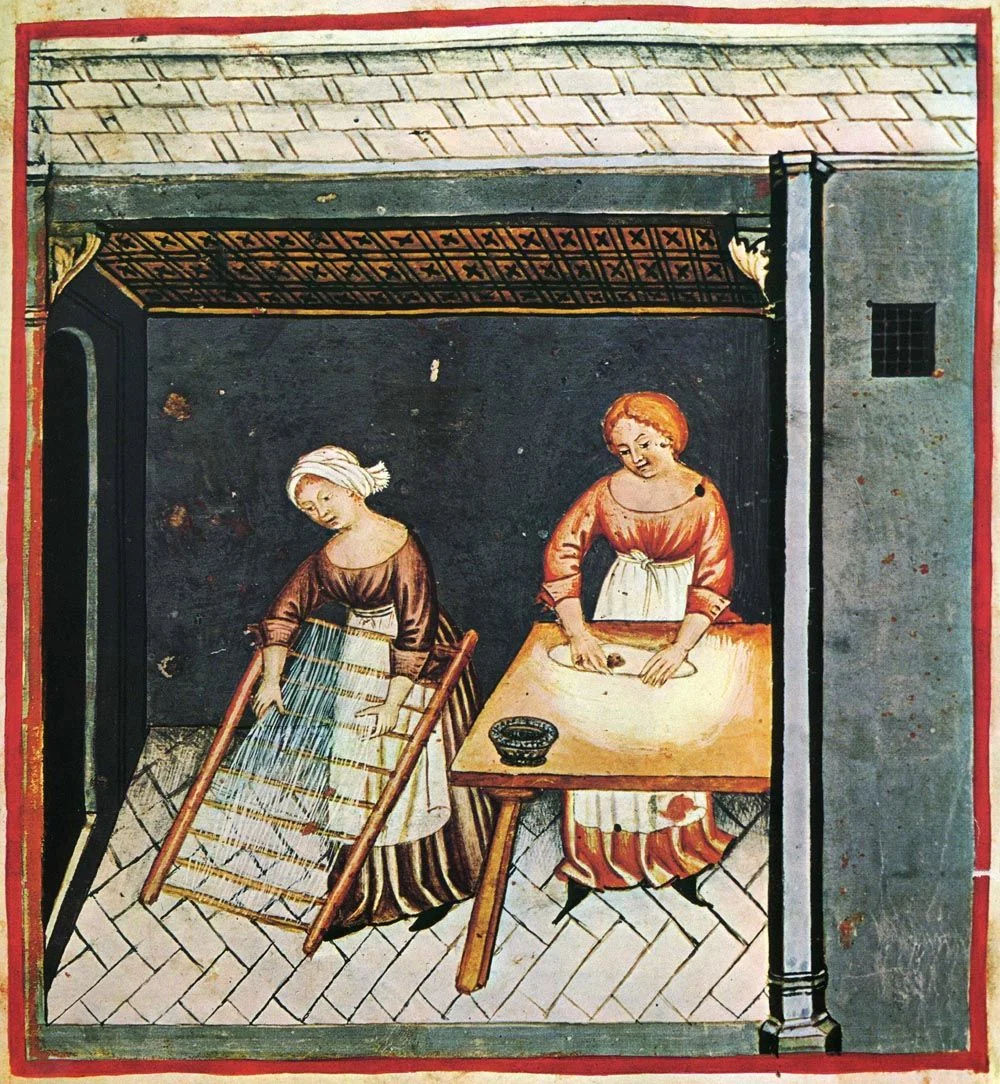

Medieval pasta making.

The spread of the fork first took place in Italy in the latter part of the Middle Ages. During this time, pasta had assumed an importance in Italy which was unknown in other parts of Europe. The technique of producing dried pasta was introduced through Muslim occupied Sicily from around 800 AD, and by the 12th century this easily transported pasta made in Sicily and Sardinia was being exported to mainland Italy and Europe. It’s in these Italian pasta-eating regions that we see the use of forks increase. In fact, until the second half of the 16th century, forks seem almost exclusively limited to those areas where pasta was eaten. Why? Probably because eating pasta with two prongs rather than one was easier, and three prongs even better.

Very slowly, the practice was adopted throughout Italy and some parts of Spain, though the fork’s use remained limited to the eating of pasta alone.

The decadent, dangerous, and womanly fork

The fork was viewed very differently outside Italy’s pasta-eating regions, and even among these prong eating pioneers the use of a table fork for eating anything other than pasta was considered unnatural and unhygienic. In England and France, the fork was seen as effeminate, an excessive form of table manners, and even dangerous. King Henri III of France was ridiculed by Thomas Artus in 1605 for his fork-wielding effeminacy after chasing his peas and beans around his plate. In neighbouring Germany, personal forks were seen as suspiciously close to the Devil’s pitchfork, with figures such as Martin Luther rallying against their use.

Traveller for the English, Thomas Coryat

But attitudes to the fork would eventually change. In 1611, the Elizabethan traveller, Thomas Coryat, reported that he had seen a custom ‘that is not used in any other country’ - you guessed it, the fork. According to Coryat, the Italians were a modern people who saw fingering the meat as bad manners, ‘seeing all men’s fingers are not alike cleane’. So he decided to adopt the practice himself, even to the scorn of his friends who referred to him as ‘furcifer’, a term meaning both ‘fork-holder’ and ‘rascal’. But Coryat, like the pasta-loving Italians, was ahead of his time.

And by 1700, less than a hundred years after Thomas Coryat returned from Italy wielding a table fork, the utensil was widely accepted across Europe.

Fork you, Martin Luther.