Let's Ketchup: A history of the king of condiments

From Asia to America. The evolution of ketchup.

A (very) brief history of fish sauce

To tell the story of ketchup, it's useful to give a brief introduction to it's predecessor, fish sauce (a full account of which can be read in a previous SECONDS post, Fish Sauce: A Fishtory.)

Not much is known about the first fish sauce. Some historians think it was produced by ancient Greeks along the Black Sea coastline, while others believe it was made by the Carthaginians on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis, in modern-day Tunisia.

Whatever the case, it was the Romans who developed an obsession with their version, which they called garum (or liquamen, muria or allec, depending on the particular type). Garum was produced by fermenting fish blood, guts and heads with lots of salt, which the Romans would apply liberally to pretty much everything they ate.

Some historians argue that fish sauce was introduced into Asia by the Romans sometime before the fall of their empire in 476 AD, though others believe Asian communities invented their own kinds of fish sauces independently. Whichever is true, across the Asian continent people went mad for the stuff.

Around the 14th century, however, China, Japan, and Korea turned away from the fishy condiment in favour of fermented bean products, particularly soy. Soya sauce became increasingly popular over the next few centuries, perhaps because it was cheaper and easier to transport than its fishy cousin, or maybe just because they preferred the taste.

But that didn’t spell the end for fish sauce.

Kôechiap, kichap, catchup

While much of East Asia had lost its lust for fish sauce, her Southeastern neighbours were still very much in love. It’s thought that during the 17th and 18th centuries Southeast Asian traders reintroduced fish sauce into the Chinese coastal province of Fujian, where it became known as kôechiap, roughly translating to ‘brine of pickled fish or shell-fish’.

The British probably came across the word via the Malay, kichap, and it became commonly known in English as catchup, or, as we know it today, ketchup.

That’s right, ketchup, in its earliest form, was a sauce without tomatoes and with fish. Lots of fermented, liquified fish. (The lack of tomatoes was probably a good thing because a large proportion of Europeans were actually scared of the fruit - which they nicknamed the ‘poison apple’ - until well into the 1800s.)

The British probably first encountered ketchup (the sauce rather than the word) in Southeast Asia towards the end of the 1600s, possibly in Sumatra. Catchup was defined as a ‘high East-India Sauce’ and was a catch-all term for many different types of sauces made with ingredients ranging from fish to soybeans.

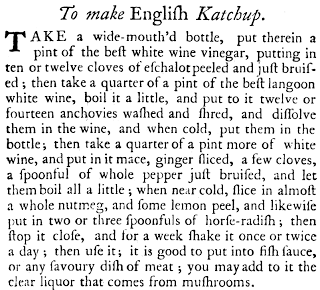

To make English Katchup, E. Smith (1727)

It didn’t take long for the first English ketchup recipe to appear in E. Smith’s 1727 Compleat Housewife; or, Accomplished Gentlewoman’s Companion. The recipe, ‘To make English Katchup’, called for anchovies, shallots, white wine, and a variety of spices. While not very true to its Asian heritage, the recipe was a huge success and appeared in cookbooks throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. This recipe also used vinegar, which would become one of the main differences between fish sauce and modern ketchups.

British cooks had to be inventive when trying to replicate Asian ketchups. Soybeans weren’t cultivated in Europe at the time, so other ingredients, such as mushrooms and kidney beans (the latter a product of the New World), were used in their place. Anchovies, having become popular in Britain in the 17th century, were incorporated into numerous sauces and condiments, including ketchup. As very few people had actually visited ketchup's place of origin, cooks were free to adapt and experiment as they wished.

The early 1800s witnessed the height of homemade ketchups in Britain which saw an abundance of recipes, including ones for beer, cucumber, elderberry, gooseberry, grape, lemon, liver, lobster, oyster, peach, plum, and raspberry varieties. Despite all this diversity, by the mid-18th century, three popular ketchup flavours emerged; fish, mushroom, and walnut. Mushroom ketchup enjoyed particular popularity, with Jane Austen being one of its many fans.

Ketchup in the colonies

Britain’s love for ketchup made it across the Atlantic to America, where the now famous tomato-ketchup combo was born. In 1812, a horticulturist named James Mease added tomato pulp, spices, and brandy to his ketchup, though he referred to the fruit as ‘love apples’. His recipe was a success and dozens more soon followed. Sadly (or happily) for the fish, it was around this time that their use in the condiment trailed off.

After the Civil War there was a ketchup boom. The New York Tribune hailed it as America’s national condiment and by the turn of the century there were 94 different brands in Connecticut alone. But its journey to the top wasn’t over, as it would soon reach new heights via its association with three major foods; hamburgers, hot dogs, and French fries.

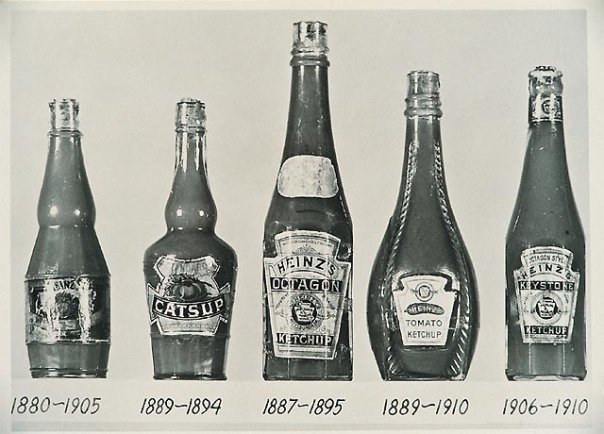

Heinz ketchup bottles from 1880 to 1910

Along with its affiliation to fast food, it would soon be linked with one particular company - H. J. Heinz. Up until the early 1900s, most ketchups were made with preservatives such as benzoate, coal tar, and other questionable ingredients. Benzoate is a food preservative, also known as E211, and is generally recognised as safe today but at the time it split the ketchup world in two; one side believed ketchup couldn’t be made without it, the other believed it could. Heinz belonged to the latter, increasing the amount of vinegar and sugar to act as natural preservatives, as well as upping the amount of ripe tomatoes used. As ketchup had always been salty and bitter, Heinz had now created a condiment that, according to some, pushed all five taste buttons; sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami.

It clearly worked. By the early 1900s, Heinz was the biggest producer of tomato ketchup in the world, with an output of more than five million bottles a year.

The condiment that conquered the world

In the past 120 years, tomato ketchup has spread far beyond the English speaking world. Last year alone, Heinz produced over 650 million bottles of ketchup, sold in more than 140 countries, with annual sales of $1.5 billion dollars.

As Andrew F. Smith, author of Pure Ketchup: A History of America's National Condiment, states, 'Few other sauces or condiments have transcended local and national culinary traditions as has tomato ketchup.' Or as food theorist Elizabeth Rozin once said, ketchup is 'the only true culinary expression of the melting pot, and . . . its special and unprecedented ability to provide something for everyone makes it the Esperanto of cuisine.'

From an ancient fish sauce to a modern mix of tomatoes, sugar, and vinegar, you're now all ketchuped.

🍅 🍅 🍅 🍅 🍅 🍅

Highly exciting and exhausting

During the 19th century, condiments such as ketchup and mayo became increasingly common. As per, not everyone was happy about it. American food reformer, Sylvester Graham, wanted to ban condiments, including ketchup, because he deemed them to be ‘highly exciting and exhausting’.

The Famous Fruit

Famously a fruit, not a vegetable, tomatoes originated in Central and South America, were brought to Europe by Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century, and finally caught on in northern Europe in the 19th century.

La tomate et le président

It was a common belief in the US during the 19th century that tomatoes were poisonous. This didn’t stop Thomas Jefferson sending tomato seeds back to America after he ate the fruit in Paris, however.

Ketchup in numbers

In the USA, around 15% of all tomato consumption is in the form of ketchup. And seeing as tomatoes make up 22% of American’s total vegetable consumption it’s relatively significant. Potatoes, on the other hand, make up 30%, over half of which are consumed as potato chips or French fries.

🍅 🍅 🍅 🍅 🍅 🍅